(p.

3)

Chapter

1

One

Tenth of America's Land

To

most Americans the Northern Heartland

has long been the most mystifying part of their

country. Spreading across the northern states,

in the deep interior of North America, from Montana to Michigan's Upper Peninsula,

from northern Iowa to the Canadian border,

the region contains about one-tenth of the total

land area of the 50 United States. It is as big

as Texas and twice as empty (or half as crowded).

In the western reaches the shopping trade

area of Miles City, Montana, includes

more land than the state of Connecticut;

to the east the local trade area of Bemidji, Minnesota, is almost as large as New York's Adirondack Mountain region.

Billboards on the edges of some small

towns proclaim plenty of room to grow.

They are always at least half-right;

there is plenty of room. In many cases they

are all right; there is also growth, some of it fast by any comparison, some of

it remarkably steady by any

comparison.

If

you fly the scheduled airlines from Seattle-Tacoma

to the Twin Cities, and on to Boston, more than one-third of the transcontinental

trip crosses this region (Figure 1). Coming

from Seattle you could mark the region's western

boundary about where you see the Bear

Paw Mountains rise a half-mile above the plains

of north central Montana. There on a summer day a dark island of ponderosa pine forest

stands above the sage- and grass-covered, deeply carved lower slopes; the whole

mass overlooks the sea of strip-cropped wheat

fields and rangeland that rolls northward into Saskatchewan. As you head

eastward

from the Twin Cities and leave the region,

you could look far to the north of your route

and imagine the boundary where the Porcupine

Mountains rise 1,000 feet above Lake

Superior. Rock ledges tower above Lake of

the Clouds. The glacier-polished rocks and the clear lake are bright openings in

the midst of a dense forest where 17 feet of snow fall in an

average winter. The northern boundary of the

region lies 250 miles north of the Twin Cities

airport. There the Rainy River spills from border

lakes that wash hundreds of miles of quiet,

rocky Minnesota and Ontario shores. In contrast, on the region's southern

edge, 150 miles south of the Twin Cities, the

upper reach of Iowa's Skunk River winds southward between gently undulating, tile-drained corn fields.

From

the Bear Paws to the Porcupines,

from

the Skunk to the Rainy, this region sprawls

over one-third of a million square miles.

What shall we call it? Perhaps the name used most widely and for the longest

period in the

region's short history is Northwest. This was the new Northwest, when the settlement frontier

was advancing across the region from the

1850s to the 1910s. It was mostly distinct from the Old Northwest—the land

east of the Mississippi and "northwest of the River Ohio," defined

by the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. While the

name Northwest was applied from the

outside, it was also adopted by insiders

in St. Paul, Minneapolis, and cities and

towns from western Wisconsin to eastern Montana. With development of metropolitan centers

at Seattle, Tacoma, and Portland, and emergence

of the name Pacific Northwest, Northwest

gradually dropped from vogue in this

interior region. Meanwhile, Central Northwest was tried, then Upper Midwest and

Northland. People from other parts of the United States often vaguely

called it the Northern Plains. Those terms

imply a unity to the region, which

indeed it has. But they also mask its

rich diversity. Because this book is in some ways a sequel to a regional study that used

the term Upper Midwest a quarter-century ago,

I shall use the same term now.1

(p.

4-5)

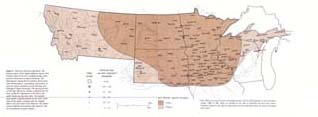

Figure 1. America's Northern Heartland. The primary region of the Upper Midwest reaches from northern Iowa to the U.S.-Canadian border, from northern Wisconsin to eastern Montana. The Minneapolis Federal Reserve banking district and some transportation, wholesaling, and services

extend the region's periphery across Montana and Michigan's Upper Peninsula. The spacing of cities on the map reflects the climatic gradients from the lush, productive Midwestern Com Belt to the colder North and the drier West. The smooth, deep mantle of glacial deposits across much of the heart of the region contrasts with the rougher plains west and south of the Missouri, the glacier-scoured uplands surrounding Lake Superior, and the mountainous western margin.

Figure 1. America's Northern Heartland. The primary region of the Upper Midwest reaches from northern Iowa to the U.S.-Canadian border, from northern Wisconsin to eastern Montana. The Minneapolis Federal Reserve banking district and some transportation, wholesaling, and services

extend the region's periphery across Montana and Michigan's Upper Peninsula. The spacing of cities on the map reflects the climatic gradients from the lush, productive Midwestern Com Belt to the colder North and the drier West. The smooth, deep mantle of glacial deposits across much of the heart of the region contrasts with the rougher plains west and south of the Missouri, the glacier-scoured uplands surrounding Lake Superior, and the mountainous western margin.

(p. 6)

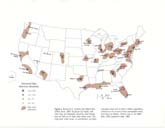

Figure

2. Church Membership as a Percentage of Total U.S. Population, 1971.

The Upper Midwest had

one of the highest proportions of church membership

in the United States, along with southeastern New England and the Mormon

West. Source:

note 2.

(p. 7)

The

Ties That Bind

To

those who regularly travel the region, do

business in it, and live in it, this is a big neighborhood,

or an empire, or perhaps both. All over the far-flung area, familiar regional names

mark chain and franchise stores, banks,

and farm cooperatives. Familiar hymnals

from familiar publishers are at hand in the church

pews (Figure 2). (With southeastern New

England and the Utah valleys, this ranks as one of the three most churched areas

in the United States.)

Familiar networks of friends and

relatives, built on the migration patterns of several generations, bridge

between the farms, the

Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul,

and the intermediate towns and hamlets

. Familiar meetings and conventions come together

most often at Minneapolis-St. Paul. And

everybody shares the concealed satisfaction

of surviving and even prospering in the world's

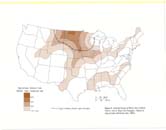

most extreme climate (Figure 3). Hot winds, arctic gales, searing drought,

dripping humidity,

dust clouds, dense fogs, tropical downpours,

tornadoes, chinooks, fence-high snowdrifts,

breath-freezing stillness, baking sun—those

tests of human adaptability occur in

various combinations in every part of the world.

But only in the Upper Midwest can you expect

all of them in the course of any normal year.2

One

measure of neighborhood is who talks

to whom and how much. Telephone connections

provide a measure of that kind of interaction,

and the Upper Midwest is a buzzing hive

of phone messages between places and people

(Figure 4). The contacts have a geographic

pattern. To be sure, there are calls from

everyplace to every other place. But the calls

from farm neighborhoods or hamlets go most

frequently to the nearest shopping and service

center. From shopping and service centers

most frequent connections lead to the nearest

larger centers of wholesale distribution,

services, and shopping. And within the region,

calls from all those places to a large metropolitan

area flow predominantly to the Twin

Cities. In a different way the professional sports

radio networks outline the region (Figure

5). While the breadth and depth of their coverage

has varied with success on the playing

fields, the networks have persistently linked

the localities in which there is enough loyalty to the regional teams to make

the broadcasts

commercially salable in the local markets.3

The

Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area

is one of 30 high-order urban centers in the

geographic structure of America's urban settlement

(Figure 6). Those 30 centers are the home

of nearly two-thirds of all the country's population.

They are the locations of nearly all of

the Federal Aviation Commission's major hub

airports. They are the main concentration of

corporate headquarters, professional services,

arts, and professional sports. Those activities

combine with their skylines to make the

high-order cities the main symbols of metropolitan

America.4

The

primary region of the Upper Midwest is that part of the United States which is

closer to the Twin

Cities than it is to any other high-order

metropolis. The pattern of phone messages

reflects this fact. And what are the messages

about? They undoubtedly reflect the sweep

and diversity and historical evolution of

the region. People are placing orders with wholesale

distributors, transferring payments,

arranging professional services, reserving

seats for games or concerts or foreign tours,

reserving hotel rooms for meetings, catching

up on the affairs of migratory friends and

relatives, and of course talking about the weather.

Sometimes the same call serves several

of those purposes. Thus the Upper Midwest is the primary trade and service

area of the Twin

Cities. The Twin Cities did not make the

region. The region did not make the Twin Cities.

The pattern just evolved in the complex process

of settling the land of the United States.

Some

strong linkages reach beyond this primary

region of the Upper Midwest. The periphery

of the region extends west into the Montana

Rockies-to Glacier Park and Yellowstone,

to the valleys of the Flathead and the Bitterroot. And it extends east across northern

Wisconsin and Michigan's Upper Peninsula to

the rapids of the St. Marys at Sault Ste.

Marie. Phone traffic from smaller towns

and cities in the periphery to the Twin Cities

is less than the flow from those places to Seattle,

Denver, Chicago, Milwaukee, or Detroit.

Yet those smaller places in the periphery are more strongly linked to the Twin Cities than

are other places of similar size outside the region.

The

region's extended periphery largely reflects

Twin Cities banking connections. With

the creation of the Federal Reserve system in 1914, regional Federal Reserve

banks were established at a dozen major cities. Minneapolis

was one because it was the larger of the

twins, and because the Twin Cities metropolitan

area at that time was far larger than any other

western or southern city except San Francisco

and Los Angeles. The national map was divided-into 12 Federal Reserve districts,

each tributary to one

of the system's banks. Then,

as now, a territory existed in which correspondent

ties between metropolitan and local

banks clearly focused on the Twin Cities. The

territory included Minnesota, North Dakota, much

of Montana and South Dakota, and northwestern Wisconsin. Banking ties in much

of that area reflected sheer proximity to the

Twin Cities. In central and western Montana

they reflected the legacy of business connections

along the Twin Cities-based Northern

Pacific and Great Northern railroads. There

were important ties in nearby northern Iowa,

too. But all of Iowa was foregone Chicago

territory in this contest. Without part of Iowa,

the population of the Twin Cities banking region was not quite enough to meet

the minimum requirement; hence more of northern Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan

were added. Metropolitan ties of those areas

then, as now, ran mainly southward to Chicago,

Milwaukee, or Detroit. But an important

flow of commerce also moved east-west along

the original Soo Line railroad, between the

Twin Cities, Sault Ste. Marie, and eastern Canada.5

(p. 8)

Figure

3. Seasonal

Temperature Extremes. Source: note

7.

(p. 9)

Figure

4. Frequency

of Phone Calls to the Twin Cities. Source: note 6. (Detailed data from 1963; intensity

adjusted on the basis of data for 1972 and 1975.)

(p. 10)

Figure

5. Professional

Sports Radio Stations and Listening

Area, 1983. The broadcast for Twin Cities

professional baseball and football teams has coincided

approximately with the Upper Midwest primary region. Source: Kaufman, note 3.

Figure

5. Professional

Sports Radio Stations and Listening

Area, 1983. The broadcast for Twin Cities

professional baseball and football teams has coincided

approximately with the Upper Midwest primary region. Source: Kaufman, note 3.

Thus

an Upper Midwest primary region reaches

from the Bear Paws to the Porcupines and

the Skunk to the Rainy. And a periphery extends

west into the Montana Rockies and east

to Sault Ste. Marie. The primary region and

the periphery, together, are the banking region.

Together they reflect the emergence of the

Twin Cities regional metropolis and the rail, trade, and financial interests historically centered there.

Of

course, the region is no monolith: it is a kaleidescope of ever-changing small

communities and

networks of people, who spend most of their time conducting local, day-today

affairs. The overlay of regional connections,

though always subtly guiding them in many

ways, directly affects only a few people's daily schedules most of the time and most people's

daily schedules rather seldom. The region's

boundaries are no knife-edge; there are gradients. Strength and frequency of the

binding internal ties decline gradually with increasing

distance from the Twin Cities. Across western

Montana the direction of dominant flows

gradually shifts to Seattle. Across southwestern

South Dakota and southern Montana the

gradients shift toward Denver. Across western

and northern Wisconsin they tilt sharply

toward Chicago and Milwaukee.6

Climatic

gradients occur as well. With the temperature

extremes that accompany location

in the continental interior, comes the reward of a predominance of bright

days. Indeed from the

Mississippi to the Rocky Mountain

foothills the region is the sun belt of the Frost

Belt. Westward across the Rockies the regimes

of sunshine, cloud, and precipitation gradually

swing toward the moderating influence of

the Pacific. Winter cold also moderates

and the growing season lengthens gradually toward the south. Eastward across the

lake

country the Atlantic regime of the northeastern United States and eastern Canada gradually

takes over, and the yearly number of cloudy, snowy, or rainy days increases.

(p.

11)

Figure

6. Busiest U.S.

Airports and High-Order Urban

Areas, 1983. Except for Las Vegas, Salt Lake City,and Memphis, all of the most heavily used

air hubs are in high-order urban areas. The high-order

urban areas, or conurbations, are daily commuter

areas with at least 2 million population, centered on one or more census metropolitan areas of

at least one million. Source: note 4. Air traffic data,

1983; population data, 1980.

(p.

12)

Figure

7.

College Students' Image of Livability. Source:

note 8, Gould and White.

Figure

7.

College Students' Image of Livability. Source:

note 8, Gould and White.

(p.

13)

Perhaps

the steepest gradient, in many ways, occurs at the United States-Canada

boundary. To be sure, the border is open, friendly, easily crossed, and frequently crossed

by many who live and work near it. Yet, to cross it and remain for long, you have to

disentangle from one web of national history and geography and weave yourself into a different one.

The two histories and geographies overlap and entwine in many ways all along

the border. But they are recorded in separate sets of records —one set

linked north and the

other south, one set ultimately to Ottawa and the other to Washington. In the settlement and

development of the Upper Midwest and the Canadian Prairies, many broad parallels and

cross-linkages emerge. Yet the balance of binding

ties today shifts very sharply to Toronto,

Winnipeg, Calgary, and Edmonton at the Upper

Midwest's northern boundary. For most

Americans the mental map of climate ends there, too. Details of seasonal and

daily variety dissolve into a uniform misconception or

a blank. Canada's federal and provincial governments

work hard at educating Upper Midwesterners

about the warm, sunny summers north

of the border. For it has been hard to get Midwestern Americans beyond

the idea that central Canada is an icebox,

from where the coldest weather comes.7

The

External Image That Segregates

While

internal ties bind the region, an awesome national mixture of disinterest and puzzlement

has segregated it. You might guess that 95 percent of Americans view the region as uninhabitable, with a climate

suitable only for testing batteries, motor oil, and pick up trucks. Most of the

other 5 percent know better because they live here or they have

lived here. Migration data make it clear that many would like to return, and

many do. Business-executive

surveys rate the Twin Cities

at or near the top among large urban areas for

quality of housing, neighborhoods, recreation, government, education, and culture. I have

heard senior officials in Washington wax nostalgic

over times they spent in "those remarkable communities" of Bismarck or

Brookings, to name two. But those are the reactions

of people who have lived in the place.

And most have not.

The

region is a blank on the mental maps of most Americans. For better or worse, no popular

image or symbol takes shape. College students elsewhere do not spontaneously think

of it as a place to live after they graduate (Figure 7). Families approaching retirement

age do not hear of it as a place for enjoyment of their later years (Figure 8). In

media stereotypes wheat ranchers are from Kansas, not North Dakota or Montana. Cattle ranchers are from

Texas, never South Dakota. Carefully shirt-sleeved

decision makers ponder printouts in

the towers of New York, Chicago, perhaps

Houston or San Francisco, not the Twin Cities.

Outdoor recreation is pursued in the mountains, in the Southwest deserts, or on subtropical beaches, seldom in the Boundary Waters

canoe country or on the quiet lakes of the North Woods. To be sure, over

the years a jumble of names has shown through

the mist-for instance, the Mayo Clinic,

Burma Shave, Scotch Tape, Glass Wax,

Sinclair Lewis, Lawrence Welk, Bronco

Nagurski, Roy Wilkins, Mary Tyler

Moore, Hubert Humphrey, and the

characters of Lake Wobegon. But such

emissaries appear to be as accidental and unusual as a chilly day in the Sunbelt.

Frequently

the national media quote someone who says "the Twin Cities are an

excellent place

to live." Thus Minneapolis-St. Paul become a vague, inexplicable anomaly amid the wastelands, glaciers,

and boondocks. The personal and

institutional emissaries and the peculiar

reputation of the Twin Cities do as much to deepen the mystery as resolve

it. As a New York cab driver said to me,

"You got a ball club there. They

got to have a place to play. So what does the place look like? Yankee Stadium and glaciers?"

Momentary visions arise, but sooner or

later the emptiness closes in again on that part of the national mental map that yawns between

the Bear Paws and the Porcupines, the Skunk

and the Rainy. At least so it seems sometimes

from the heartland!8

Varied

Environments

In

fact, 6 million people do live in the primary region of the Upper Midwest, 8 million in

the banking region. They live in natural environments

with vivid variations from one part of

the region to another—environments which

do, indeed, have a lot to do with glaciers (Figure

9). Those different environments not only

offer the reality to fill the void that exists in so many imaginations, but also provide the stage

on which the real story of the region's settlement has unfolded.9

THE

FOREST ZONE

On

the east and west the region is framed by two of the great wooded regions of the United

States—the northern Great Lakes and the northern Rockies. The Great Lakes forest—the

North Woods to 40 million Midwesterners who live and work to the south of it

— shades the Upper Midwest

east and north of a line from Lake of the

Woods to the Dalles of the St.

Croix River, northeast of the Twin Cities, to north-central

Wisconsin.

(p.

14)

Figure

8.

National Image of Where Not to Retire. Source:

note 8, Boyer and Savageau. (Based on map

of

rated

retirement sites, 1984.)

(p.

15)

Figure

9. Upper

Midwest Natural Environments. Source: note 9.

(p.

16)

Cropland, partly improved pasture strewn with glacial boulders, and the ever-present forest

backdrop, in the northern Wisconsin countryside between the Twin Cities and

Wausau, are typical of the eastern part of the Upper Midwest. Photo by

author.

Today

the forest is a crazy-quilt. Each patch

is a grove dominated by one of many species-spruce,

pines, balsam, tamarack, birch,

aspen, oaks, maples, and other hardwoods.

In the brief autumn patches of a brilliant variety of reds, browns, and golds

flash among the evergreen, and for a

week or two the quilt becomes a

masterpiece. At that time, on a clear

late afternoon, it is worth the price of

a plane ticket to Duluth or Houghton just to see

the quilt in aerial panorama.

Each

patch has its story. In part the patches

reflect the stages in the botanical succession

as each particular piece of the forest recovers from its most recent cutting or

burning,

invades the derelict clearing of an abandoned

farm, or grows in the neat rows of a new plantation.

In part, also, the forest patches reflect

the random pattern of sand, clay, gravel,

boulders, and bog that make soil mapping on

these glacial moraine deposits a cartographic

nightmare. Disorderly heaps and terraces

and saucers of glacial material form the land

surface everywhere beneath the trees. But there are natural openings at the thousands

of lakes and ponds and a few openings, too,

where geologically ancient bedrock protrudes

as bald hilltops through the glacial drift.

Water

is in abundance. Dependable summer

rain and winter snow supply the moisture.

Cool summers reduce direct evaporation and the amount needed by growing

vegetation. As a result the subsoil is

moist. The lakes are full. Closely spaced, dependable streams meander

and tumble from lake to bog as they head

for Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, or the Mississippi.

(p.

17)

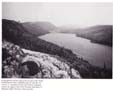

Ice-age glaciers scoured a deep trench for Lake of the Clouds and polished the hard, half-billion-year-old rocks that

surround it. A mixed forest of pine and northern hardwoods mantles the rugged terrain of the Porcupine Mountains, in Michigan's Upper Peninsula. Photo by author.

In

the northern part of the Great Lakes forest

zone, the land rises in massive waves toward

the great Canadian Shield. Made of some

of the oldest, hardest, and most mineralized rock, the Shield forms the high

ground of central

and eastern Canada. There the continental

glaciers of the ice age accumulated, and

from there they spread chaos south to what

is now the Ohio and the Missouri. The southern

edge of the Shield is in the Upper Midwest,

in the wilderness of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area and the Voyageurs National

Park of northeastern Minnesota. As the elevation

falls toward the south, only the higher

ridges of hard rock protrude through the

mantle of glacial deposits. Several of those ridges are the famous mineral

ranges - the Me-sabi and Vermilion of Minnesota; the Gogebic, straddling

the Wisconsin-Michigan border; and

the Copper, Menominee, and Marquette ranges

of Upper Michigan.

The

most impressive ridge is the great geologic

fault scarp that forms the north shore of Lake

Superior. Behind the clean pebble beaches

and headlands, the country rises a thousand feet or more to the north horizon. Offshore

a few miles the lake is nearly a thousand feet deep. Off the south

shore another ridge, nearly submerged, rises

faintly above the lake level to form the Apostle Islands. In summer

the deep, cold lake, towering ridges, and

rocky islands create anomalous narrow strips

of maritime environment in the heart of the

continent-always cool; with ample wind for

sailing; sometimes fog-shrouded; with a long, mild growing season that is

especially gentle for flowers of

forest and garden. In deep winter the scene takes on the character of the wildest coast of Lapland

—crashing waves amid driving snow

with a southeast wind, grotesque

giant ice curtains and stalactites, colorful pebble beaches encased for miles like souvenirs

in a sheet of ice laid exquisitely by breaking waves, days when arctic sea smoke

rises in whisps as far as the eye can see while the

open lake steams beneath subzero air blowing from somewhere near the North Pole.

(p. 18)

Nearly

1,000 feet deep a few miles offshore from this point, midway

betwen Duluth and the Canadian border, the open water

of Lake Superior combines with a subzero arctic gale to create a unique,

awesome midwinter scene. Photo by author.

The

other forest realm covers the western part

of the region. As you move toward the west,

it first appears in islands of ponderosa pine

on the great isolated earth crustal domes called

the Black Hills or the Big Horn, Bear Paw,

Big Snowy, Belt, and Crazy mountains. Farther

west the forest is nearly continuous in the

corridor of crustal upheaval named the Rocky

Mountains, from Yellowstone to Glacier Park and beyond. Most of the forest

lies above the 4,000-

to 5,000-foot contours, up to the

timberline at 9,000 to 10,000 feet. In that range

of altitude, both moisture and summer heat

are adequate. Not only is the forest more dense

and tall in the main ranges of the Rockies,

but also it is more varied. West of the continental divide stands of douglas

fir and lodge-pole pine

turn your thoughts toward the Pacific

Northwest. Winter snow, spring and autumn

rains are more reliable, thanks to more direct

exposure to moisture from the Pacific.

The

highest water yields in the region come from

the mountain forests and the barren

jagged peaks and snowhelds above them. Most

of the water pours out in torrents during the spring melt and spring

rains. But some soaks in to saturate the

forest litter and rocky slopes, then seeps out gradually during the warm

season. All of it feeds the clear upper reaches

and the muddier, lower main stems of famous

tributaries of the Missouri and Columbia. Below the forest, grassy benchland

slopes to the Great Plains on the east

and into the broad valleys between the

main ranges — especially the

spectacular trenches of the Bitterroot and Flathead. In the classic western

settlement pattern, cities, towns, and

irrigated ranches lie in the wider

valleys. Old mining towns and locations

string along certain canyons. Logging roads and scenic highways lead to camps

and cabins of

exurbanites and to the edges of wilderness

preserves in the mountain forests.

(p.

19)

THE

CROPLAND CORRIDOR

The

wide plains between the two forests are

the agricultural realm of the Upper Midwest.

The heart of the agricultural country is in the

prairie-glacial drift plains corridor. It trends

southeast-northwest from northern Iowa

to northern Montana. That corridor shares, with

the rest of the North American Middle West and

Great Plains and perhaps three or four regions on other continents, the world's finest

upland soil resource for modern farming technology. The land was mostly treeless

prairie at the time of white settlement; hence nature spared farm settlers

the costly work of clearing it. The

soils are formed on deep, fresh glacial

deposits, generally high in soluble mineral

plant food. Deep, dense roots from millennia

of prairie grass growth made the soil initially

high in organic matter and nitrogen. Though

a few boulders remain, not yet decomposed from glacial times, the material is

mostly a thick blanket of clay, loam,

and silt.

But

some important differences emerge within

the corridor. South of roughly the latitude of the Otter Tail River in

west-central Minnesota

and the Sheyenne in southeastern North Dakota, the growing season is long enough

for grain corn, and soybeans. Eastward

from the wide, level valley of South Dakota's

James River, the spring rains are ample

and fairly dependable. Summer rains are fickle

but adequate in most years. This warmest,

best-watered part of the prairie-drift plains

forms the Upper Midwest's part of the American

Corn Belt and the richest part of the Upper

Midwest agricultural base. Nature boosted

the settlers there to a head start, and subsequent generations of farmers have parlayed

their inheritance from the pioneers.

North

of the Corn Belt, a sizable part of the cropland

corridor is one of the most remarkable

of legacies from the ice age, the Red River Valley.

Of the great lakes ponded against the edge

of the retreating glaciers in central Canada

10 millennia ago, the greatest was Lake Agassiz.

The lake was named long after its demise,

of course, for the Swiss-Bostonian naturalist

Louis Agassiz. It covered a large part of what

is now eastern North Dakota, northwestern

Minnesota, and Manitoba. It rose to the height

of a divide along the present Minnesota-South

Dakota boundary and spilled over the

divide, southeast down a mile-wide trench now

occupied by the Minnesota River Valley. When

the ice finally disappeared, the lake emptied

northward through Hudson Bay to the sea. The

vast lake floor, mostly clay and flat as

a pancake, was then exposed to the sky and quickly

covered with a carpet of prairie. And so it lay until large-scale white

settlement began in the 1870s. Two brief, catastrophic events

in the long history of the earth have created

today's landscape there: the melting of the last ice sheets and the nineteenth-century spread

of European people. From the air today you see a fantastic landscape of

unbroken, flat, checkerboard fields. In summer the fields are square miles of wheat,

square miles of potatoes, square miles of barley, square miles of oats

or blue grass or sugar beets. The continuity

and scale of the checkerboard overwhelms all

but the larger urban centers in the landscape,

while it sustains them as thriving nodes in

the regional economy. Though smaller and less

moisture-retentive, the plain along the James

River through South Dakota is the second

of these two major islands of flat land on the

rolling prairie.

West

of the Red and James valleys the climate is drier. Rains fail occasionally in

spring, frequently in

summer. The climatic break comes

near the meridian of 100 degrees west longitude.

The Hundredth Meridian is the classic

boundary of the semiarid West in much of

our literature and official lore. Farmers near Lawrence

Welk's hometown, southeast of Bismarck,

live close to that meridian. They could show

you prairie land shaped by the glaciers that

is just as smooth as much of the Corn Belt. But their reliance on wheat and barley rather than

corn reflects their lesser confidence in the moisture

supply. As the glaciers pushed southwest into drier, warmer country, they

thinned and stalled on long, high ridges

that trend northwest-southeast on the plains. The longest

and highest of those —the Missouri Coteau

—still carries the name the French explorers gave it. Chaotic small hills,

intervening shallow prairie potholes,

and boulder fields pock the surface.

Those are the features of glacial

moraines, where the glacier's edge stood vacillating

for hundreds of summers. The rate of

ice advance equaled the rate of melting at the

front; as a result the glacier just kept hauling in and dumping load after

load of dirt and rock along the same line. Today the potholes fill

to the brim in a wet spring. But during perhaps

half of the summers in living memory, drought and evaporation have left many of

these low areas as mere flat white beds of cracked

alkaline mud. Nineteenth-century school

geography maps used the label "Region of

Salt Waters." That was the way the area looked

to surveyors who saw it during the 1860s.

But the larger, wetter potholes provide way

stations for tens of thousands of waterfowl

on the plains flyway between the Gulf of Mexico

and their Canadian nesting grounds. North

Dakota farmers on the Missouri Coteau could

explain how they avoid potholes and the worst

boulder fields, leaving those areas for grazing

and waterfowl habitat.

(p.

20)

Outbuildings

make up a large livestock feeding operation in south-central

Minnesota in the early 1980s. The black soil evolved

beneath natural prairie grasses that mantled much of today's

Upper Midwest cropland corridor before white settlement.

Trees in the picture are all planted shelterbelts around the farmyards.

Photo, Frederic Steinhauser.

In

the drier wheat country west of the Hundredth Meridian, strips

may be cropped in alternate years to conserve moisture on

the gently rolling uplands. Where river valleys are incised into the plains, grass and sage sparsely mantle the sharp ridges,

cedars pock the rocky ledges, and cottonwoods and box elder

follow the narrow draws. This view is north from the breaks of the

Yellowstone River in eastern Montana. Photo by author.

(p.

21)

This

southeastern Minnesota valley, west of LaCrosse, Wisconsin, lies in the

stream-dissected, unglaciated part of the transition

zone between the cropland corridor and the Upper Great

Lakes forest. Steep, wooded valley walls separate the fertile, rolling ridgetops

from the rich bottomlands several hundred feet below. Photo, Frederic

Steinhauser.

West

of the country around Havre and Great

Falls, the prairie-glacial drift plains broaden

and flatten again in an area Montan-ans call the Triangle, between the Missouri,

the

Rockies, and the Canadian border. This is the

type locality of the famous warm chinook winds

of midwinter. Rainfall and snowfall are a

little more reliable than on the plains to the east.

The Sun and Marias rivers, and numerous swift creeks, bring irrigation water

from the

neighboring mountains. With more moisture

and milder winters, ranchers in the Triangle

grow nearly half of Montana's wheat.

THE

TRANSITION ZONES

A

narrow transition zone separates the main

cropland corridor from the Upper Great Lakes

forest realm. The transition zone is widest

and most unusual—for the Upper Midwest-southeast

of the Twin Cities, through southwestern

Wisconsin and northeastern Iowa. By

chance the ice-age glaciers bypassed this

area. As a result, splashing rain and streams

have had more than a hundred million years

to carve its surface into treelike networks of

valleys and intervening ridges. The land is unglaciated

and stream-dissected. The upland fields,

on fertile but thin soil, command panoramic

views across waves of high, rolling ridge

tops and deep ravines. Clean limestone cliffs

and intervening steep slopes of rock waste

form the valley walls. Rich hardwood forests

darken the north-facing bluffs and ravines, while cedars dot the

otherwise open goat prairies on drier

southwest-facing slopes. On the bottoms the rich floodplains and terraces

support cropland, and the tributary rivers

wind rather steeply toward the Mississippi.

On the western, drier side of the transition zone, before agricultural

settlement, prairies covered the ridgetops

as well as the south-facing slopes. Scattered groves interrupted

the tall grassland. But on the less drought-risky

eastern edge of the zone, only scattered

openings of prairie interrupted the dominant

woodland. The lovely islands of prairie and grove inspired scores of place-names

across the transition zone in the Upper Midwest.

(p. 22)

Rough, lake-studded glacial moraine land in the Park Region of west-central Minnesota is typical of much of the Dairy Belt, on the northeastern margin of the Upper Midwest's cropland corridor. Photo by author.

Rough, lake-studded glacial moraine land in the Park Region of west-central Minnesota is typical of much of the Dairy Belt, on the northeastern margin of the Upper Midwest's cropland corridor. Photo by author.

In

Minnesota, from the southernmost lake district

at Albert Lea to the most northwesterly lake

district around Detroit Lakes, the forest-to-prairie

transition zone lies on the remarkably varied surface of the Upper Midwest's most

extensive and roughest glacial moraines. From the tops of 100- or 200-foot

knobs, early explorers

could see for miles across a lush, rolling

compage of hills, lakes, prairies, and woodlands.

For good reason, they called it the Park

Region. The name still fits the landscape, although

the prairies are now pastures or fields.

These transition areas are the historic heart

of Upper Midwest dairy farming.

North

of Detroit Lakes the big moraine loops

eastward into the forest zone. But the forest-to-prairie

transition zone continues northward

across the international boundary, along strings of low, sandy beach ridges that

once formed the shores

of great Lake Agassiz. Groves of aspen and openings of prairie, at the time

of white settlement, made the transition between

wooded beach-ridges among vast bogs

in the forest zone to the east and the flat prairies

of the Red River Valley to the west.

Another,

very much wider and very different transition zone spreads westward from the

Missouri. South Dakotans call it West River

country. North Dakotans call it the Slope and

might tell you it's the section of the state with

rattlesnakes. Summer tourists speeding from

Chicago to the Black Hills get a feeling that

this is where the West begins.

(p. 23)

A

midwinter view looks southwestward across the wide Missouri

in south-central South Dakota. The stream's crevassed ice

cover separates the smooth veneer of glacial deposits, black prairie

soil, and checkerboard of corn fields on the east side from

West River ranching country. To many travelers, this is where

the West begins. Photo by author.

The

general elevation begins to rise subtly from

the Missouri toward the Black Hills, Big

Horns,

and Rockies. Meanwhile, like the Upper Mississippi Valley below St. Paul, the trans-Missouri

country was mostly beyond the reach of the

ice-age glaciers and their smoothing

veneer of drift. The face of the land reflects

the work of the master rivers that flow from

the mountains and Black Hills to the encircling

Missouri. Their names are legendary in the West-the Yellowstone,

Musselshell, Big Horn, Powder, and Tongue,

the Little Missouri, Cheyenne, and White, and the smaller Knife,

Heart, Moreau, Grand, and Bad. Except

for the Yellowstone, these are slender streams, for they drain the driest

part of the northern Great Plains. But

without harassment by continental

glaciation, there has been time for a quarter-million hundred-year storms to pound and erode

their watersheds. The result is a series of

deep, wide, rugged trenches radiating from the high country toward

the Missouri, and along the Big Muddy. Valley

walls are generally covered with prairie and

sagebrush. The

surface is harsh but resembles velvet in shadowy panorama when the

sun is low. In a few spectacular places, the soft, colorful, geologically young

bedrock has washed

easily and has seldom stabilized long enough

for the plant cover to take hold. Those are

the Badlands. The rivers are widely spaced,

for it takes a lot of land to catch enough water

to make a river in this dry country.

(p.

24)

Gently

rolling plateaus project toward the Missouri between the breaks of tributary valleys.

With no glacial deposits to mask them, local

buttes and pine-edged escarpments rise above

the plateaus. They are landmarks on always distant skylines. To the early

scouts they first intimated the mountains beyond the horizon

to the west, and later they provided guideposts to wagon trains on the trackless

prairie. Today you

might get the local names for

those features from ranchers, as you survey

the hve-square-mile expanse of each one's wheat

fields or rangelands.

Global

Forces —Natural and Human

The

active powers of nature have created this

varied stage for Upper Midwest settlement.

The stage is the product of global flows of

air, water, and the earth, itself. The global flow

of air makes a dramatic and dynamic climate

today (Figure 10). Daily television and newspaper

maps tell that story. Two of the three most

frequent positions of the atmosphere's west-to-east jet stream across North

America converge from Alberta and Colorado

to the Great Lakes. The low pressure centers

that follow those routes swing their continuous

procession of fronts, with accompanying temperature changes, cloud, and

precipitation, across the Upper Midwest.

Those

converging storms and jets draw air from

three of the world's most contrasting sources

across the region's forests, fields, lakes, and settlements. One source is the Canadian

Arctic. Air from that source is cool in summer,

frigid in winter, and always antiseptically

clear, to let the northern lights, stars, and

sun shine brighter. A second source is the Tropical

Atlantic. Moist air streams from there westward

across the Gulf of Mexico, north up the

central lowlands, and into the passing lows

and fronts. Storms lift it to form the mountainous

thunderheads of summer and the leaden,

layered clouds of winter. Then the storms

wring from those clouds the downpours, blizzards, and drizzles that water the land.

Those tropical maritime airstreams often reach the Upper Midwest at the surface east of the Hundredth

Meridian in spring and summer, but west of

the Hundredth Meridian only occasionally

and mainly in the springtime. They

seldom reach the region at the surface in winter but spread over it aloft to

produce most of the winter's clouds

and snow. The third source is the dry

western plateau country, between

the Rockies and Sierra-Cascades. That source

is cool in winter, hot in summer, and always dry. Passing storms draw its dry air into the

Upper Midwest frequently as far east as the Hundredth Meridian, less

often into the eastern prairie region as far

as Minnesota and Iowa. In winter

continental incursions are the warm chinook winds of the High Plains and the

less frequent thaws of the eastern areas. In

summer they are the spells of hot winds which

bring searing temperatures and, if they persist long enough, wilt sapling

trees and turn fields to dust. Only over the

high mountain country do these air masses give up some of

their meager water content, from sheets of winter clouds and

summer-afternoon thunderheads.10

Thus

the global wind system today differentiates

the region into a northeastern province

of cool, moist summers and cold, snowy winters;

a subhumid prairie province east of the

Hundredth Meridian; a semiarid short-grass prairie province west of the Hundredth Meridian; and the moist high

country of the mountains and Black

Hills. In the ice ages of the

geologic near-past, a similar global wind system prevailed. But temperatures fell enough that in the cool, snowy northeastern province

the snow accumulation in the longer winter became more than the sun and

rain could melt during the shortened summer.

For thousands of years the

accumulation deepened, compacted, and began to spread. The spreading

sheet stalled when it moved south of

the major jet streams into realms of warmer or

drier air, or both. Thus the same location in the

global air flow that creates Upper Midwest weather

patterns today created the glacial patterns

that left their imprint on so much of the land in the ice age.

The

global flow of water takes the moisture

delivered from the ocean surface by the atmosphere

and returns it to the oceans down the

Missouri and Mississippi, the Columbia, the

Red, and the Great Lakes (Figure 11). But in the interim, like the flow of air,

the flow of water differentiates the Upper Midwest into contrasting

realms. Rain water and snowmelt partly

soak into the soil, partly run off directly to

the nearest stream. The soak-in first nourishes the cover of crops, range, and

forest. Whatever remains fills the

ground water reserve and seeps

through springs to the streams as

indirect runoff. If none remains, then no springs or streams flow in the

long periods between annual spring melts or

infrequent severe summer storms. If

there is not enough soak-in to support

a forest, there is no forest. Thus the vegetation cover and the stream flow reflect the rainfall, snowmelt, and water budget of

the region.

(p.

25)

Figure

10. The

Upper Midwest's Position in the Flow of Air

across North America. Low pressure centers

that follow the northern paths of the atmosphere's

jet stream swing their procession of fronts across the Upper Midwest, with

accompanying clouds, rain, and winter snow. They draw air from three of

the world's most contrasting source regions.

Source: note 10.

(p.

26)

Figure

11.

Flow of Water in the Upper Midwest. Runoff

from the land is a measure of the sustained annual supply of water available for

direct human use.

Some of the runoff is stored for days or centuries

in the ground and in lakes and wetlands. Rivers

carry all that remains to the sea. For comparison,

municipalities in the Twin Cities metropolitan

area use about 75-100 billion gallons per year

— equal to the average annual runoff from

an area about 30-35

miles square in the Mississippi

headwaters country, or 4-5 percent of the river's

average flow at Minneapolis. Sources: Mark W.

Busby, "Annual Runoff in the Coterminous United

States," in Hydrologic

Investigations Atlas

(Washington, D.C.: U.S. Geological Survey, 1966);

supplementary data for several small basins from

USGS annual Water

Resources Data.

(p.

27)

In

early spring the Baptism River pours 20,000 gallons of water

per second, from a 1,000-square-mile drainage basin in northeastern

Minnesota, over the escarpment along Lake Superior's north shore. Photo, David

Borchert.

In

late spring the Powder River brings a few hundred gallons of water per second

from a 20,000-square-mile basin on the Great Plains. Pine-edged buttes rise

above the dry grassland on

the horizon in southeastern Montana. Photo by author.

(p.

28)

In

a dramatic expression of the conjuncture of global forces, the

forested Rockies rise above the treeless plains on the region's western

periphery in central Montana. Photo by author.

The

cool, moist northeast and the western high

mountains are also the realms of forests and

lakes and the sources of large, dependable rivers.

The subhumid, somewhat drought-riskier

prairies east of the Hundredth Meridian

are also the source of smaller rivers and a land of fewer lakes. The semiarid western plains

were clothed in only a shortgrass prairie; today they support only more

drought-resistant crops and send out only meager, widely

spaced rivers.

Even

the gradual flow and heaving of the earth's

crust are reflected in the giant folds, faults, domes, and basins of the western

mountains; in the

massive subcontinent of ancient

rock that forms the Canadian Shield; and in

the mineral veins injected into fissures during

eras of great crustal disturbance (Figure 12).

Crustal shifts are also reflected in the broad

basins, filled with miles-deep layers of sedimentary

rock, which lie beneath the plains of

Dakota and eastern Montana. Some of those rocks are oil- and coal-bearing and

provide the large

reserves of the Powder River, Knife River,

and Williston basins.

People

have set the stage and changed the scenes

with comparable drama —and also through

processes as inexorable and evolutionary

as nature's. Suppose you were to talk with

the people whom you inevitably would encounter

if you were to go out to look at the different

natural environments of the Upper Midwest.

Loggers in the northern Wisconsin forest

might talk about their forbears who were

Chippewa Indians living in the region when white explorers, missionaries,

traders, then loggers, townspeople, and

farmers arrived. Taconite mill workers on the Mesabi Iron

Range could tell you about their Finnish forbears

who migrated to the Lake Superior district

when the Czar was imposing a tightening

tyranny on their homeland in the early 1900s.

(p.

29)

Figure

12.

Upper Midwest Mineral Resources. The deposits reflect the history and location

patterns

of the gradual flow, heaving, and fracturing of

the earth's crust through geologic time. Sources: James

Turnbull, Coal

Fields of the United States

(Washington, D.C.: U.S. Geological Survey,

1960), sheet 1; Oil

and Gas Fields of the United

States (Penn-Well Publishing Company, 1982),

note 9, Gerlach.

(p.

30)

Farmers

in the Iowa Corn Belt might tell you

about their German grandparents; a Red River Valley family, their Norwegian and French

Canadian backgrounds. One family on the

Missouri Coteau in North Dakota could talk

about the Russian-German settlement there

in the 1890s, and another in the Montana ranching

country might recall their great grandparents'

stories of their trek from Missouri

after the Civil War. An exurbanite couple in

a Montana mountain cabin might discuss their

real estate business in California and their

parents' immigration from Italy to New York.11

The

varied settlement map of the Upper Midwest

reflects flows of people whose individual

decisions have been motivated and constrained

by massive migrations, social and political

movements, conflicts, famines, and tyrannies

in many corners of the world. At the same

time, of course, their individual decisions

and actions added up to these very same movements,

migrations, and conflicts. There-suit

has been a continuing avalanche of events with

tumbling momentum and lives of their own.

Mean while-within the world's established

networks of settlement, transportation, and

communication-streams of information, inventions,

goods, and capital constantly flow to

and from the region and within it. Those flows continue to change the maps of

the region's population, employment, income, and

connections. The environment is dynamic.

The region is a product of the convergence of

global natural and human forces.

Little

more than a century ago the Upper Midwest

region was an embryo. Most of the land

lay beyond the American frontier. In a century it became a prosperous, integral

part of the world

economy. The region today is a complex

network of farms, small towns, cities, metropolitan

areas, and connecting routes.

So,

those who pose serious questions about the

region seek to understand that remarkable

transformation. What accounts for the

Upper Midwest's location, shape, and look?

What has been the anatomy of its initial development? Of its adaptation to dramatic national and worldwide

changes? Why and how much has the region's identity persisted amid

so much change?

One

way to try to comprehend the process of

change is through geographical snapshots of the region's settlement at different

times. Three times are

especially critical. Around 1870

American Indians sparsely occupied the land.

The white invasions of the Upper Midwest on a

large scale had just begun. The growth of the

United States as a major steel producer

and the steel rail era of transcontinental railroad building had just begun.

By 1920 the occupation of the region

by whites was essentially complete.

The Northwest Empire had been

created. The era of the automobile, airplane, cheap oil, and electronic communication

was just emerging on a large scale. In

the 1970s and 1980s, products of the era

that began around 1920 are in place: industrialized

agriculture, metropolitan settlements,

highway-air-electronic networks. The empire

has become in many ways a neighborhood

in an increasingly unstable, intense, worldwide

circulation system.12

In

the 1980s we are now entering a stage of unprecedented

growth of awareness of the worldwide system and its complexity.

Those three widely separated times frame two major epochs for understanding the

Upper Midwest: an epoch of development and rapid population growth between 1870 and 1920, and an epoch of great adaptation and economic growth between 1920 and the 1980s. The two periods, in sequence, also provide some background for us to think about further change and adaptation in another period,

beyond the 1980s.