(p.139)

Chapter 6

Reorganizing the Cities

Community

responses to boom and adversity were

reflected in the changing maps of individual

cities. Booms were accompanied by explosive

expansion and drastic geographical reorganization.

In the auto era, urban land and floor

space grew two or three times as fast as population.

The effects of simple population growth were multiplied and complicated by increased travel, exchange, and material consumption.

In the country as a whole, while the number

of households tripled, trade and service employment grew sevenfold, and floor space

per person more than doubled. The avalanche

of personal vehicles, and the space needed to accommodate them, soon became obvious

and gradually became legendary. But, aside

from personal vehicles, the sheer physical

volume of goods stored and used by an average

household increased at least ten fold. Per-capita

use of outdoor urban space for schoolgrounds,

playgrounds, and residential lots rose in similar proportions.

Meanwhile,

the effects of obsolescence and decline were more extensive and more visible

than they had ever been before. The railroad era had brought a vast increase in economic

activity and wealth and, consequently, in the amount of construction. By the

1970s, railroad-era

structures still accounted for more than one-fourth of the buildings standing in the

nation and in the Upper Midwest. A half-century of auto-era changes in technology and

geography

had hastened the obsolescence of most of those structures. A high proportion of

them

were poorly maintained, worn-out, or even abandoned. Never before had a generation

of Americans found itself living amid so many

buildings and other structures which logically

called for demolition, better maintenance, replacement, or rehabilitation. Demolition

was usually nobody's responsibility. Maintenance

required more money than the occupants

of most old or obsolescent buildings could

afford to spend. Replacement structures were

usually built in more accessible or attractive

locations. Rehabilitation depended on a strong,

persistent demand for an old location. All of those problems were present in

every settlement, and they were isolated in stark relief

in areas of population decline.66

Growth Centers in the Prairies and

the Plains

Maps

of the change in five cities from 1920 through the 1970s illustrate the auto-era's reshaping

of growth centers outside the Twin Cities. Fairmont, Minnesota, was a strong-growth,

medium-size shopping and service center in the Corn Belt (Figure 45). Fargo-Moorhead,

Sioux Falls, Bismarck-Mandan, and Billings were leaders among the places that

emerged as new census metropolitan areas (Figure 46-49). Their populations grew from

three- to sevenfold during the half-century,

and their subdivided, urbanized areas grew at more than twice that rate.

its limits, it also dramatically reshaped itself to meet

the explosive increase in land requirements.66 Expansion of city limits responded at first

to accelerated auto-era growth in directions of previous development. With the

general increase in affluence, residential growth concentrated in the established directions

of high-value housing—on the right side of the tracks, that is, on the downtown sides

of river

or rail-yard barriers to city traffic flow, and toward the natural amenities of high ground

or lakeshore. Thus residential growth pushed

mainly south and southeast in Fairmont,

north and south from downtown Fargo, southwest

from downtown Sioux Falls, north in Bismarck, and west in Billings.

(p.

140)

Fairmont, Minnesota, and its chain of lakes contrast with their Corn Belt

suroundings, about 1980. The lakeside site is typical of many small towns and

cities in the eastern half of the Upper Midwest. Pioneer settlers built at the

present downtown location (center). In the 1880s, the railroads ran east

to west at the north edge of downtown. A century of residential growth expanded

away from the tracks and parallel to the lake shores. Photo, Fairmont Photo

Press, Inc., Fairmont, MN.

(p.

141)

Figure 45. Land

Use Change during the Auto Era: Fairmont, Minnesota. Most residential growth

followed the pre-auto middle- and upper-income bias away from the railroad

tracks and near the lake shore. Industrial and commercial expansion sprawled

along the outskirts in the areas with best highway and rail access. Source: note

66.

(p.

142)

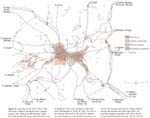

Figure 46. Land

Use Change during the Auto Era: Fargo-Moorhead. Residential growth expanded away

from the railway corridors, north and south from the central business district

in Fargo, south in Moorhead, with high-value areas mostly following the narrow

belt of natural woodland and miniscule local relief along the Fargo side of the

Red River. Exponential growth of the city's already large farm supply and

wholesale business resulted in explosive development on the outskirts,

especially along the western freeway bypass. Source: note 66.

(p.

143)

Figure 47. Land

Use Change during the Auto Era: Sioux Falls. Residential growth expanded mainly

in the established southwest middle- and upper-income sector, later to

previously remote areas opened by freeways. Rail-oriented industrial-commercial

areas exploded from the old core near the falls to the edges of the city.

Source: note 66.

(p.

144)

Figure 48. Land

Use Change during the Auto Era: Bismarck-Mandan. Residential expansion spread

mainly in the established middle- and upper-income sectors north of the railroad

corridor to high, rolling prairie. Residential growth on lower, flat land south

of the tracks was generally later, somewhat less, and aided in part by flood

control projects on both the Heart and Missouri. In large part because of the

flood control and one landown-• ing family, major commercial expansion was

kept close to downtown Bismarck, while the remainder focused, more

characteristically, on the freeway interchange location on the outskirts.

Source: note 66.

(p.

145)

Figure 49.

Land Use

Change during the Auto Era: Billings. While population grew sixfold, the

subdivided or built-up area expanded by nearly 11 times, following the level

benchlands and probing the

canyons along the broken edge of the High Plains. Downtown rebuilding has been

accompanied by outlying development of shopping centers and commercial strips.

Warehouse-industry growth

exploded from the area around the downtown railway stations to extensive

highway-trackage areas well outside the rail-era city. Source: note 66.

(p.

146)

City

limits were also enlarged to accommodate industrial expansion along the railway lines

leading into and out of the city. Those developments were often explosive in scale because

of the land needs of modern one-story factory and warehouse buildings, trucking, parking,

and sometimes even landscaping; and they usually pushed in directions away from

high-value residential land. The results are evident in the developments east from the business

center of Fairmont, in the remarkable lengthening

and widening of the rail-industry strips

along the historic Northern Pacific main line through Fargo-Moorhead,

Bismarck-Mandan, and Billings, and in the

extensive flatland development northwest of the old rail-industry

core of Sioux Falls.

Further

letting-out of corporate limits and dramatic reshaping resulted from freeway and highway

building. Most of the major highways bypassed the rail-oriented, older, congested

city. That avoided an immediate, obvious disruption of the existing patterns of land use

and circulation, and it held down right-of-way acquisition costs for the highway

departments.

But it gradually became obvious that avoiding long-term disruption of the old

city was

impossible. The new bypasses became the major force in the location of

industrial expansion,

airport development and related hotel construction,

and major shopping malls. Nearly every

mall was located at an interchange

in the direction of major high-value residential growth. Thus it could easily

penetrate the most lucrative market in the older

city,

capture the trade from the largest and most affluent areas of auto-era expansion, and

invade

the trade areas of neighboring smaller towns. In some cases, the new highways also spurred

development of attractive residential land that had been avoided throughout the railroad

era because it was on the wrong side of the tracks or the wrong side of a river barrier.

Now new large-scale subdivisions ignored previous constraints, leaped over old

outskirts or slums, and capitalized access to new, highway-oriented

job locations. The results of those forces

are evident in the development patterns

of all five cities.

The

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers also played

an important role in three of the cities. At Fargo-Moorhead, on the flat Lake Agassiz plain,

their dikes flood-proofed the land next to the low banks of the Red River of the north. The

dikes not only protected the pre-1920 city but also encouraged development of the open lands that

followed the river into the countryside both north and south from the old core of

Fargo

and far to the south and southeast of central Moorhead. In Sioux Falls, the army engineers

dug a canal to divert the Big Sioux River from its sluggish, sinuous course almost entirely

around the city. The canal bypassed the falls and dumped floodwaters into the

deeper valley

downstream from the city. In this fickle climate, near the semiarid margin of the Midwest,

the flood risk from occasional spring and summer

storms far outweighed the water-power

advantage from a small, unreliable river.

Though it was the reason for the city's location, waterpower was long outmoded and unimportant.

But the flood risk was an important problem for airport and industrial

development on the flatland northwest of

the city. At Bismarck and Mandan, the

giant Missouri River dams had

stabilized the flow of the river. As a result, potential industrial lands

were flood-proofed in Mandan. On the Bismarck side, former sloughs and frequently flooded,

unused bottomland

became the location for a new public zoo,

recreational areas, and marina.

Slightly higher floodplain land immediately south of the central business

district became a feasible area for urban expansion. The result was

a major redirection of growth which partly restored

the centrality of the rail-era downtown.

Enlarging

and reshaping those growing cities was

clearly a complex community task. The

larger cities added an average of 100 to 200 acres

of new land per year. Even Fairmont added

an average of perhaps 40 acres per year. Land

was subdivided, permits issued, buildings erected, streets and

utilities extended. The community had to

orchestrate a continuing procession

of development decisions, actions, and reactions—both public and private, local

and regional. Such a process had characterized

city building from the beginning; but the

rate, scale, and number of actors increased sharply in the auto era.

In

the midst of each booming city there was also decline. The cities had been turned insideout.

The original central areas became museums of the rail and streetcar era: derelict railway

stations, wall-to-wall multistory buildings with narrow frontages, little parking space

—all separated from the freeways by many congested blocks. As the threat of deterioration

became clear, leaders in the cities began in the 1950s and 1960s to try to define

the

problems and the community actions that looked practical. Fargo and Moorhead

were among

the country's first cities in their size classes to enter the long, trial-and-error

struggle

toward central area renewal. Organized city and private actions came a little later in Sioux

Falls, Bismarck, and Billings. Large outlays of private and government funds,

both local

and federal, helped to stimulate the activity. The results were extensive clearance of marginal

business blocks and fringe residential

areas; experiments with assistance in relocating

people and small businesses; rehabilitation;

street improvements; and construction

of public buildings, high-rise apartments,

hotels, office buildings, and new retail developments. The task is still far from complete.

The reasons for delay are familiar: abundant,

good-quality new housing on the open land

in the outer areas; difficult access to central

areas from the freeways; railroad blight; difficulty

in bringing together enough large institutions

to generate a downtown office boom.

The development process was controversial

and educational. The need became clear

for not only a long-term strategy but also a

long-term community-wide commitment, a great

deal of money, and two or three decades of

time. On a smaller scale, Fairmont joined dozens

of other cities in rehabilitating and redeveloping its original central area.

(p.

147)

Figure

50. Land Use Change

during the Auto Era: the Copper Range. The map reflects the loss of more than

half of the 1920 population, together with the abandonment of mines on the

upland ridges and smelters on the waterfront. Abandoned railroad mileage exceeds

the arterial highway mileage. The settlement pattern has evolved from a

constellation of mining, smelting, and port locations, each with nearby workers'

neighborhoods, to a system of scattered residential clusters of commuters,

pensioners, and local service employees, centered on Houghton and Hancock.

Source: note 66.

(p.

148)

Transformation of Lake Superior Cities

Maps

of the Copper Range complex and Duluth-Superior present a much different picture.

Changes in the Copper Range reflected both the total loss of the original economic base

and the partly counteracting gains from tourism and interregional income transfers by state

and federal governments through Social Security, medical programs, education, and construction

projects (Figure 50).

From

1920 to 1980 total population of dozens of small mining locations plummeted from

53,000 to 23,000. In the mid-1980s, the remains of those compact, pre-auto villages were strung along today's highways

and back roads and also along miles of abandoned railroad grades. Some

nineteenth-century, frame miners' houses and tiny clumps of brick business

buildings were still in use. But on many vacant lots only a few overgrown foundations and cellars

remained. Some of the mine locations are marked today by one or two houses or

a historical plaque. On the surrounding ridges

and swales, the cutover landscape of stumps,

brush, and saplings has given way to a

revived forest that once more softens the horizons and hides the excavations and waste-rock

dumps.

While

some of the remaining houses showed signs of

dilapidation and austerity or poverty in the 1980s, the majority had been maintained and modernized with income from jobs in the principal range cities, logging, or

tourist trade. The history and the cool Lake Superior

climate attracted summer tourists from

sultry cities to the south. Autumn leaves, hunting,

and exceptionally deep snow for skiing

drew visitors from the same markets in other

seasons. Small flocks of former residents and

their descendants, returning for village and

township reunions, added to the summer tourist

inflow. Scores of Copper Range expatriates gathered at places where

only a handful live today, to recall or learn

about old times. They came from California, Texas, the urban

Midwest and Northeast, and the retirement

colonies of Floria, as well as many other places in the United States and

abroad.

Perhaps

the most striking monuments to the past mining booms were at Calumet, near the northern end of the

Copper Range. Partly devoted to boutiques and exhibits in the early 1980s,

the sprawling cavernous stone shops and offices of the once-mighty Calumet and Hecla

Consolidated Mines brooded over several hundred partly subsided acres of derelict railway grades, foundations, waste-rock

dumps, and rusting frames. Hundreds of miles of partly collapsed,

water-filled tunnels honeycombed the underlying bedrock. Nearby, impressive

blocks of monumental brick and stone buildings reminded curious visitors that

the downtown once served a local market of 20,000 inhabitants. The frame homes that remained

around the downtown in the 1980s housed scarcely 1,000. A monument on the library

grounds recalled the philanthropy of Alexander Agassiz, the Bostonian who ran the Calumet

and Hecla after the Civil War. In the 1870s, at about the time Minnesota naturalist and

historian Warren Upham was naming glacial Lake Agassiz for Alexander's father, Louis,

Alexander was donating civic improvements to his temporary hometown out here

on the

frontier. Local place-names such as Atlantic Mine, Boston, and the famous Quincy Mine reflect

the early importance of Boston capital and initiative in the Copper Range. The resulting

philanthropy came to rest more on the Harvard

campus than in the Range. And most of

the earnings —perhaps inevitably—moved into

America's massive, fast-growing stream of

investment capital through Eastern trusts.67

In

contrast with most of the other places, the

population of Houghton-Hancock was steady

from 1920 to 1980, at about 12,000. Employment

in retail trade held barely constant, while service-employment doubled. Service employment

growth reflected in part the rising

tourist trade, but other factors even more. There

was diversification and expansion of the historic state college of mining

technology and expansion of medical

and social services by both federal

and state governments. Especially

important were services to the elderly, who made up a large part of the Copper Range population. Along the once-busy

ship channel, extensive restoration

in the 1980s was changing

the face of Houghton's downtown.

(p.

149)

Great lakes and ocean cargo ships ride on lower St. Louis Bay, the harbor of

Duluth-Superior, on a summer day in 1983. Grain terminals are prominent in the

lower foreground on the Superior waterfront. Duluth's general cargo and grain

terminals occupy Rices' point (center). The main entrance to the harbor (upper

center) cuts through Minnesota Point, which protects the bay from the open water

of Lake Superior. Duluth's

redeveloped waterfront and downtown lie to the southwest (left) of the base of

Minnesota Point. The central and eastern residential districts of Duluth climb

the escarpment to the forested, rocky highlands of Minnesota's Arrowhead

Country. Iron and coal docks are out of the picture to the west (left) and east

(right). Photo, Basgan Photography and Seaway Port Authority of Duluth.

(p.

150)

Figure 51.

Land Use Change during the Auto Era: Duluth-Superior.

Harbor, lakeshore, transportation routes, and open land dominate the vast area

within the city limits. Growth areas have been relatively small and abandonment

extensive in the pre-auto rail and heavy industry areas of Superior and western

Duluth. In contrast, substantial new growth —based on service jobs —has sprawled

among the stunted groves and tamarack bogs and captured spectacular panoramic

views, on the rocky uplands above central and eastern Duluth. Source: note 66.

(p.

151)

The

Copper Range had a drastic change in urban

structure from 1920 to 1980. It lost almost

as much population as some of the large, fast-growing

urban areas of the Upper Midwest

gained. Census population data suggested

a debacle. The visible ruins added to that impression.

Yet, eventual depletion of the copper

ores was always a certainty. Earnings from

exploiting the deposits have been spread among

a vast and varied array of developments

worldwide. The people who lived on the

Range in 1980, and those who returned for summer

reunions, were both intellectually and

materially much better off than the immigrant

laborers and perhaps even their schoolteachers,

ministers, doctors, and merchants

in the rough-and-tumble settlement of the

1860s and 1870s. For thousands of families, the

Keweenaw was a way station on geographically

twisting, economically upward paths from

scattered origins in Europe to equally

scattered destinations in America. While

they lived and toiled there, they contributed

to the world's swelling stream of capital.

We can only speculate or wonder what the situation

would be if the people and capital had been less mobile.

The

Twin Ports of Duluth-Superior presented

a more striking picture of maintenance

and growth amid obsolescence and abandonment

(Figure 51). Centerpiece of the urban

area in 1980 was still the spacious harbor. A nineteenth-century whaleback

freighter near the

modern hotel and yacht basin on Superior's

waterfront is only one small part of the

harbor's living museum.

Some

of the great, dredged promontories on

the bay were vacant and overgrown, edged by

rotting pilings, washed by the waters of quietly

silting slips. Hundreds of acres of railway

yards were used at a fraction of their capacity.

Other hundreds of acres were virtually abandoned.

Nearly 5,000 transportation jobs had disappeared between 1929 and 1980, as trucks

took over a large share of the grain traffic

and new railway equipment reduced turnaround

time for grain, coal, and iron shippers.

Near the head of the bay, the steel mill was

cold and rusting away—as it did while hundreds

of jobs disappeared during its last decade

of operation. The neighboring cement plant

was silent because it lost its source of raw material when the steel mill closed.

Yet

there was much activity at scattered locations

along the sprawling harbor. Even in a depressed steel economy, millions of tons

of taconite pellets moved through the ore docks in

western Duluth and the southeastern outskirts

of Superior. Tens of millions of bushels of

grain moved through the elevators on Rice's Point

and along the Superior waterfront, and a

new terminal transshipped Montana coal to the lower Great Lakes. Duluth's post-World War

II general cargo terminal on Rice's Point served

dozens of freighters at the upper end of the

Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway. Widely

scattered industrial plants, including a large,

new papermill, enlarged on nineteenth-century

traditions in wood- and metal-working.

There

was also much uncertainty. Changing

steel requirements and foreign competition made iron pellet shipments more variable. The volume

of grain shipments was also increasingly

variable as more of the flow was directed

to international markets, with resulting competition from Pacific and Gulf

ports. The general

cargo port was competing against the much

larger market and more frequent sailings at

Chicago. Post-World War II residential

expansion in areas around the bay had

been miniscule. Much of it had been in the vicinity of Morgan Park - once a

planned company community, designed

and built at the time the steel mill

opened in 1910. Though the mill was defunct, the carefully designed residential

area had kept its amenities and enhanced its status.

In

contrast with many port-rail-industry areas, maintenance, or even growth, was prevalent

in other districts —notably central and

eastern Duluth. Employment had grown on

the campuses on the east side, in the services

and light industries downtown, and fitfully

around the airport during temporary periods

of military expansion. On the downtown

Duluth waterfront, some of the big, mul-tistoried

buildings that housed the great hardware

and grocery wholesalers at the turn of the century

were subdivided, rehabilitated, and partly

occupied by a new generation of light industry

and offices. Impressive rehabilitation and

redevelopment was gradually lifting the face of the railroad-era business district. Energy

for those improvements came from generous

federal construction grants as well as the downtown

economic base. The central and eastern

high-density residential area had expanded

one-third since 1920. Additional low-density

development had sprawled across another

dozen square miles. The expansion resulted

from replacement. Although the net total of metropolitan population growth was near

zero, new housing in the central and eastern

heights had continually replaced deteriorated

housing in the old cores and industrial west

end. Newer dwellings had replaced perhaps

one-third of the units in use in 1920.

(p.

152)

With

the help of generous federal and state

funds, a network of modern highways and

spectacular bridges was gradually stitching

together the sprawling and varied metropolitan

patchwork; and a long-enduring planning

program kept nudging the pieces into place.

The

Twin Ports in 1980 presented an unusual

and dramatic view of the powerful auto-era

thrust of service growth, federal and state expenditures,

industrial transformation, and international interdependence. Because the metropolitan

area was not buried in layers of recent

growth, it offered an exceptionally clear exposure

of the obsolescence and maintenance

problems that have beset most cities in the

auto era. The problems have not been unique to

the Twin Ports, only more prominent because

of the slow counteracting growth. Nor

was the growth experience here unique

among America's more than 300 metropolitan areas. In the years since 1920,

only eight have experienced such

chronic non-growth as

Duluth-Superior. But 30 more have experienced little or no growth during three

or four consecutive decades, and

another 130 have had one or two decades of nongrowth. The

historical geography of the northeastern United

States and other areas around the North

Atlantic is replete with cases of prolonged nongrowth of cities. The record

suggests that the Twin Ports

might feel an occasional

resurgence, but it also suggests that their

nongrowth experience could be shared by

many other cities in the coming decades. The Duluth-Superior communities were indeed

coping with obsolescence. But they were also

running an urban laboratory experimenting with the future.68

The

Regional Metropolis

In

all the transformation of the Upper Midwest

in the auto-air-electronic age, the most dramatic

and intense changes came in the regional

metropolis. The changes incorporated

both boom and obsolescence on massive scales.

In the auto era, the Twin Cities area absorbed

half the net out-migration from the rest of

the Upper Midwest. It accounted for more than

half of the employment and population growth

in the entire region. Its daily commuting area in 1980 covered more than

10,000 square miles.

In many ways the metropolis had

become a region in itself.69

In

a little more than half a century, the urbanized

area - including the scattered subdivisions

on the outskirts —grew from 160 square miles

to 880 (Figures 52-53). Population of the urbanized

area grew from 670,000 to 2 million. The

total outlay for construction of all kinds was

more than $20 billion at the prices current at

the times of development. In constant 1980 dollars,

the investment was probably over 40 billion.

If it were to be replaced at 1985 standards

for roads as well as residential, commercial,

and public structures, the outlay would surely

exceed $60 billion; and those figures do not

include the cost of interest on borrowed money.

The building took place along 3,000 miles

of new streets and roads on about 500,000

parcels of land into which the 1920 farms

had been subdivided. Thus the billions were

invested as a result of hundreds of thousands of decisions of families,

corporations, and

governments. It was a kind of community project;

almost everyone was involved. Together

they created an outer city, surrounding the

older inner city.

Auto-era

expansion has taken place in three stages:

the building boom of the 1920s and

the following hiatus of the Great Depression

and World War II; the post-World War II building

boom (and baby boom) from 1945 until

about 1960; and the subsequent period of maturation

of the outer city.

THE

1920s BUILDING BOOM

This

boom was the first in American history

to be affected by automobiles, and even then their potential impact was still in

some doubt for many

investors. In the Twin Cities, most

auto-era development before World War II

followed the directions of earlier streetcar expansion.

In fact, much of it filled in vast areas

in the outer parts of Minneapolis and St. Paul

that had been subdivided in the previous boom

and not yet built upon. But there were suggestions

of other changes that would come in the future

on a massive scale. Abundant credit

encouraged construction of new dwelling

units faster than new households were formed.

As a result, there was a high rate of replacement building, and the

surplus new units could replace old ones

which could then be discarded. While

new areas boomed, it was possible to abandon some of the least desirable,

oldest housing. The abandonment showed up in

the city residential cores. It reflected

the accelerated obsolescence of many older

houses, with primitive wiring and piping, on small, crowded lots.

Central heating and garages had become standard; and burgeoning

demand for major appliances had created

the need for modern plumbing and wiring.

With

the 1920s skyscrapers, the downtowns

were building more upward than outward.

The result was a widening "gray zone" of

accelerated obsolescence and some abandonment

in the older housing stock, surrounding

the downtowns. Then the first large department stores to be located

outside the downtowns opened their doors in

connection with the giant Sears and

Montgomery Ward mail-order houses in south Minneapolis and in

the St. Paul Midway. Thus the forces of change had appeared, but they

were slowed by the 1929 crash and the decade

of the Great Depression that

followed.

(p.

153)

Figure

52. Land Use in the Twin Cities, 1920. The Upper

Midwest metropolis was a compact streetcar city. Most of its 670 thousand people

lived within about 80 square miles focused on the job locations in the

main railroad corridor from north Minneapolis to South St. Paul. The halo of low

density settlement on the outskirts reflected the scant beginning of automobile

commuting. Except for the streetcar and summer cottage suburbs around Minnetonka

and White Bear lakes, the bountiful supply of shoreland and rolling glacial

terrain was still used for farming. Source: note 66.

(p.

154)

Figure 53.

Land Use in the Twin Cities, 1980. The streetcar city

was engulfed in more than 800 square miles of auto-era subdivision and

development. Homes and work places for an additional 1.3 million people had

spread over former farmland and along rural lakeshore of 1920. A 500-mile

web of freeways had extended and reinforced the rail transportation network.

Source: note 66.

(p.

155)

THE

POST-WORLD WAR II BOOM

Explosive

growth erupted in 1946, following

fifteen years dominated by depression and wartime

austerity. Employment was growing rapidly. There was pent-up demand from the

long period of under-building. The Congress insured

liberal home-financing credit for veterans,

who accounted for most males in the family-forming

age group. And this time almost every household owned an automobile. To

be sure, the automobiles could not get out of

the city very far or very fast on the remarkably

primitive highway system of that time. At the

end of World War II, no more than three dozen

narrow, mostly two-lane paved roads reached

even 10 miles outside the Minneapo-lis-St. Paul city limits. As hundreds of

feeder streets were graded for burgeoning

subdivisions, congestion began to develop

on the limited number of arterials.

Nevertheless, it was a big

improvement over walking from the end

of the streetcar line in the 1920s. In 1920 only 250 square miles of land area

lay within one hour of travel time, by a combination of trolley

car and walking, from the nearest downtown.

With auto travel, the one-hour area

exploded to about 2,000 square miles. As a

result, hundreds of previously inaccessible square

miles had suddenly come into the urban

real estate market. The consequence was relatively

cheap land, larger lots, and lower density

compared with earlier expansions — the

sprawl of the 1950s.

In

the frenetic effort to grade streets, run electric

power lines, complete homes, and do basic

landscaping, there was little time or money

left over. First priority for the remaining

funds went to building elementary schools as the baby-boom youngsters reached

age six. Most of the remainder went to pave the streets and

equip playgrounds. Residential growth advanced

well ahead of employment. Suburban businesses consisted mainly of building-supply

yards and convenience retail centers. Many

of the centers were little more than enlarged

hamlets from the recent agricultural past.

Growth also ran far ahead of sewer and water

extensions. At the peak, about 300,000 people

in the first ring of suburbs were dependent

on their own wells and septic tanks.

When

the baby boom ended about 1958, a sea

of single-family homes had filled all the partly

developed outskirts of the 1920s and pushed

a few miles farther into the countryside. The main thrusts followed level land

north and south from

Minneapolis, into southwestern

St. Paul, and surrounded a few old streetcar suburbs. Most builders stayed with

flatland to hold down excavation costs, or near

the edges of older municipalities for access to water systems. But most of the

fast-growing suburban population was using inadequate roads and city streets to reach central-city jobs, doctors, shopping, and entertainment.

Downtown crowding, sewer problems,

highway needs, and school construction were demanding further

attention.

MATURATION

AND CONTINUED GROWTH

Meanwhile,

new forces had been gathering

through the mid-1950s and emerged dominant

in the 1960s. An unprecedented rise in real

income was affecting most households in the

Twin Cities, as it was in the nation as a whole.

The Exploding Metropolis had yielded to The

Affluent Society as

best-selling nonfiction. Suburbs had emerged as a major market, labor force,

and tax base with large, urgent demands.

Freeway plans were nearing completion, and construction of the network was under

way in the late 1950s. With those plans in mind, Dayton's department store in Minneapolis built the world prototype enclosed suburban

shopping mall, Southdale in Edina. General Mills and 3M began to create two of

the nation's earliest suburban corporate office and

research campuses. Freeway construction sparked

much more highway improvement. As the new network gradually approached completion

through the 1960s and 1970s, more and

larger shopping malls, office parks, and industrial

parks developed near the main interchanges. The belt freeways, girdling the metropolitan

area, interconnected the new mass of homes,

shopping areas, and job locations.

The belt lines also joined the entire suburban

ring with the major radial highways that led not only inward to the downtowns

but also, more importantly, outward

to the rest of the region. The outer

city could now become a new focus for

both the metropolitan area and the

regional economy.70

Long-gestating community improvements

soon accompanied the highway and business

investments. Suburbs initiated large, new

sewer and water systems. Suburban school

districts consolidated and built mammoth new high schools. Suburban congregations

moved from temporary quarters in grade schools,

quonset huts, and taverns to monumental

new churches.

schools,

quonset huts, and taverns to monumental

new churches. The Airports Commission

made its first round of massive improvements, and Wold-Chamberlain Field

became Twin Cities

International. The new suburban municipalities

built civic centers, libraries, and fire

stations to replace sagging, nineteenth-century,

wooden rural town halls. Finally, city and

county parks, private and public golf courses,

and state junior college campuses occupied

some of the remaining gaps in the development

pattern.

(p.

156)

Central Minneapolis, viewed from east to west in 1983, was in transition. The

falls of St. Anthony-constrained by dams and concrete aprons, bypassed by

locks-and the historic bridging point at Nicollet Island lie upstream from the

center of the picture. The transcontinental rail corridor was busy, but large

old yards were being abandoned in response to changes in railroading and

pressure for redevelopment. Once a child of the falls and rail lines, the

downtown had become a focus in the freeway system and the locus of massive new

construction and rehabilitation. The expanded University of Minnesota campus

straddled the river between the downtown and the major concentration of grain

elevators (foreground). Aerial photo by K. Bordner Consultants, Inc.,

Minneapolis, MN.

(p.

157)

Also in transition was central St. Paul, viewed from northeast to southwest,

1985. Oversize parking ramps for automobiles from today's converging freeways

occupied the riverside location (left center) of the former Union Depot train

sheds-once the focus of the region's rail network. With the river dammed and

dredged, and the entire frontage improved, the original landing below the Union

Depot was an inconspicuous spot amid barge fleeting and pleasure craft

operations. New towers rose among restored, old structures in the downtown core.

Around the edges, extensive redevelopment and rehabilitation combined to change

the face of "Lower-town" (lower center), the state capital area

(right), and the hospital-public arena complex (above). Aerial photo by K.

Bordner Consultants, Inc., Minneapolis, MN.

(p.

158)

Amid

these changes, support rose for coordinating the public improvement programs

of the scores of local governments, state agencies,

and special districts that made up the

metropolitan area. Together they were using

public revenue collected by local, state, and

federal governments to build the basic skeleton

of the outer city. The support grew out of

both the frustrations of the frenetic boom

years and the obvious, growing management problems now that the community was

catching up with the backlog of major public

construction. Thus the Minnesota legislature

created the Metropolitan Planning Commission in 1957, then strengthened, broadened,

and renamed it the Metropolitan Council

in 1967. Within a short time, the council

had to make influential decisions on eventually unsuccessful proposals to build a new super-airport

on the Anoka Sand Plain and to build

a new subway system focused on the central-city

downtowns. Both projects would have made important shifts in the location of public capital investments within the metropolitan

framework, whether or not they would

have affected the overall pattern of growth. The council then produced its metropolitan development guide in 1970 and first defined

the urban services line, to limit the rate and

sprawl of the sewer and water network, in 1974.71

The

housing market also changed in the 1960s.

The array of choices became more diverse

as the share of new housing construction in single-family units dropped from

nearly 100 percent in

1955 to about 60 percent during the following

decade. Apartments, then condominiums,

made up the other 40 percent. Also, the replacement rate rose to an

unprecedented level.

That is, new houses continued to be built at

a high rate, although the rate of new household

formation declined. As a result, more people

all the way down the housing chain could

move up into new quarters more quickly,

and old housing at the bottom of the chain could

be abandoned at an unprecedented rate. Most

of the new housing was built in the outer city,

and virtually all the abandonment of older

and dilapidated housing was in the inner city.

THE

NEW OUTER CITY

By

1980, a new outer metropolis indeed existed.

It had been built to accommodate 1.7 million people, or more than half a million

households, with

automobiles. It included all the suburbs plus the post-1920 edges of the central

cities. It spread across rolling land, around

hundreds of lakes and ponds, among tens

of thousands of acres of woodlands, with abundant parks and playgrounds. On its

inner margin were the

major parks which had been developed

from farmland nearly a century earlier,

and 50,000 acres of recently created regional

parks and preserves lay in its outer margin.

The new outer metropolis was bound together

by the nation's highest per capita metropolitan

freeway mileage and a highly developed

grid of arterials. The outer city focused

on eight major shopping malls and the vastly

upgraded metropolitan airport. It also included

several sprawling assemblages of offices,

hotels, and industrial parks around the principal

interchanges on the belt freeways.

Of

the one million jobs in the metropolitan area in the early 1980s, more than half

were located in the

auto-era outer city. Metropolitan area

retail sales rose from $1.3 billion in 1958 to $7.3

billion in 1977. But in the same period, the downtown

shares of the total had fallen to 5 percent

in Minneapolis and one percent in St. Paul,

while the major shopping malls had captured 12 percent. Fifty-two percent of

all sales were in the

garish suburban commercial strips,

where there had been virtually nothing in

1920. In addition to hundreds of new firms, nearly

300 industries from Minneapolis and nearly

50 from St. Paul had moved to more spacious

quarters in suburban industrial parks between 1960 and 1977. In 1982, the

auto-era ring

contained 31 million, or well over half of the 58 million square feet of

metropolitan area office space less than 15 years old. The downtowns

were home to the office headquarters for

most of the largest business firms with the greatest assets and also for the

largest government

offices. But the suburban ring, with generally

lower development costs, housed more of

the young fastest-growing firms and the greatest

number overall.72

Impressive

as the outer city had become, older

parts here and there were already beginning

to come unraveled. Some early post-World

War II commercial strips were obsolete. Their

locations had poor access to the freeways,

vacancy was high, building maintenance

was neglected, and parking spaces were broken

and weedy. The giant sports stadium, opened

in the late 1950s, replaced in 1982 by the

downtown Minneapolis dome, was abandoned

and awaiting eventual clearance andredevelopment.

Schools built for the baby boom

of the 1950s were redundant.

(p.

159)

Twin Cities International Airport, 1983, grew from a grass field and small

frame hangar on the site of a defunct auto-racing track of the 1920s to be one

of the country's major hub airports. The complex occupies the flat peninsular

plateau east of the Mississippi (upper right) and north of the Minnesota River

(bottom). Historic Fort Snelling stood at the confluence, just east of

the present airport. Several square miles of sprawling runways, ramps,

terminals, and major airline headquarters made up the air-age version of the

rail-era downtown depots, yards, and railroad company offices. The airport

succeeded the rail terminals, the riverboat port, and the old fort as the fourth

generation of regional transportation nodes. Office-industry-hotel developments

(lower left) follow the freeway about seven miles west to the Edina interchange,

shown in the following picture. Aerial photo by K. Bordner Consultants, Inc.,

Minneapolis, MN.

(p.

160)

The nearly uninterrupted level plain south of downtown Minneapolis (upper

right), which accommodated most streetcar-era growth, contrasts with the

rolling, lake-studded moraine land, the scene of most auto-era expansion.

Roughly the lower two-thirds of the area pictured in 1984 was built up since

World War II. Western and southern legs of the first belt freeway around

Minneapolis intersect in Edina and Bloomington, in the foreground. The

high-rise concentration in downtown Minneapolis (top center) is eight miles to

the northeast. Aerial photo by K. Bordner Consultants, Inc., Minneapolis, MN.

(p.

161)

NEW

ATTENTION TO THE INNER CITY

In

the center of the 800-square-mile suburban

ring lay the 50-square-mile inner city, entirely

within Minneapolis and St. Paul. To be sure,

all the inner city was not literally pre-auto. Although all of it was subdivided

and settled before the

auto age, parts of it had been rebuilt

at least once. The downtowns were the scene

of frequent though fitful and partial replacement

of old buildings by new ones almost

from the beginning. There have been major

redevelopments over the years in some of the

central cities' outlying districts, notably the Honeywell

headquarters complex, the hospital

zones, the University of Minnesota campus,

and the public clearance and housing projects.

But

redevelopment had accounted for less than one-tenth of the inner-city area. From

the 1920s through the

1960s most of the pre-auto city

had been the scene of creeping obsolescence

and abandonment. The obsolescence was coupled

with deferred maintenance on many buildings

and streets. Abandonment was coupled

with deferred clearance or redevelopment. There was a general spreading of

low income and low investment.

The

situation was the result of a stubborn syndrome

of problems. Except for the federally

financed interstate freeways, highway improvements

did not penetrate the inner city "lump."

Even the interstate freeway penetration

was slow. Higher welfare and police costs accompanied the changes in

population and land use, while costs also

rose for even minimal care of aging improvements. Those expenses

kept real estate taxes high. And before anything new could be built, costly demolition and

removal had to take place. Consequently, in

competition with the suburbs, inner-city land

suffered from less accessibility, higher taxes,

and higher land preparation costs for new development. In one way, the lump of older,

obsolete structures was part of the pervasive

American solid waste problem. Unlike cans

and bottles, the buildings could not simply

be tossed out of sight. But they could be left behind

as the metropolis turned its back and faced

outward. Yet, if you believed that the Twin Cities metropolis was here to stay,

perhaps you had to

believe that this relatively small

area in the middle of it merited recycling.

Beginning

in the late 1950s, strong counterforces

began to develop and converge on the

inner-city malaise. They came from different

sources, partly related, partly coincidental. Together their effects were

truly impressive.

With 90 percent federal financing, the interstate

freeways penetrated the inner city in the 1970s. Costs had been high and delays lengthy

because of the need for demolition, resettlement,

and compensation for a wide range

of unprecedented social, economic, and physical

damages. But eventually the freeways

restored metropolitan accessibility to the downtowns.

The freeway plans, coupled with other

federal aid opportunities, sparked comprehensive plans for redevelopment. The

St. Paul Capitol

Approach plan took on new life, and

the Minneapolis Metro Center plan evolved

rapidly. Basic hopes and themes reappeared

from the proposals of a half-century earlier—monumental

central-city cores, riverfront

development and beautification. This time

action quickly accompanied the planning.73

City

government, large corporations with local

control and inner-city headquarters, major

hospital and medical centers, and neighborhood

resident organizations soon joined in the

effort. Major developers were attracted from

other centers of investment capital in the United

States and Canada. The city governments and specially created authorities funneled

federal subsidies to target areas. Money went

to realign and improve streets, build parking

ramps, improve public buildings and parks,

and subsidize new housing and home improvements as well as subsidize interest

rates on bonds for new major construction. The

cities borrowed heavily to buy land, clear it,

prepare it for new development-and to make

accompanying public improvements and

embellishments. The private organizations, in turn, made heavy

commitments to new construction. And the

neighborhood organizations labored

to keep a share of the public

improvement funds flowing into residential areas and a share of the subsidies directed to family

housing. Plainly, with the complexity of

the script and the diversity of actors, a great deal

of learning and negotiation was necessary to

evolve the plans and translate them into action.

The resulting boom has been peaking in the

1980s.

Meanwhile,

in the late 1970s the post-World

War II baby-boom generation entered the

housing market. That happened at a time of

unprecedented national inflation. With building

costs high and interest costs rising, the new generation could not do what their

parents had done in the housing crisis of the late

1940s: go to the outer fringe and build a rambler.

Instead, they turned inward. They bought

into the vast, older housing stock in the

transition zone between inner and outer city and set out to improve it. Thousands of households were soon burning

the lights late at night, pouring "sweat equity" into older houses

and yards, just as their parents had with

new ones three decades earlier. While public

outlays were important in bringing new life

to those older neighborhoods, private outlays

were far greater. Although most of the activity

was the result of average young families renovating average old houses, some

involved higher-income young families renovating fine old

mansions and gentrifying historic, once-prestigious neighborhoods near the edges

of the downtowns and

in the lake districts. Thus the central cities' ring of deterioration was shrinking

and even partly dissolving in the 1970s.

A new wave of downtown improvement

and gentrification was pressing against it from the inside, and a wave of

house-painting, cabinet-installing,

carpet-laying younger families

pressed from the outside. As a result, abandonment came virtually to a halt, and

there was more crowding

of the lowest-income and the transient

populations.

(p.

162)

A

historic preservation movement also converged

on the inner city in the 1970s. If housing

is an indicator, the average life expectancy

of a building in the United States is about 80

to 100 years. The first large wave of construction

of monumental buildings in the Twin

Cities began with the rise of the Northwest Empire after completion of the

northern transcontinental

railroads. That was in the 1880s

and 1890s. Eighty to 100 years later, Twin Citians faced for the first time the

abandonment and

destruction of hundreds of architectural monuments that commemorated important

people and institutions in Upper Midwest

history —office buildings, warehouses,

churches, homes. Consequently, other

forces coalesced on the stage. At first there were protests and rallies. Then buildings were surveyed

and classified. City and federal tax subsidies

were aimed at helping private investors

restore high-priority, well located structures.

The oldest, most durable, monumental, and

well-situated structures were in or near the

downtowns. For at least the first round of historic

preservation, the major targets were in

the inner city.74

As

a result of these converging forces, the inner

city in the 1980s was probably in the best physical

condition in its history. Increasingly the

downtowns were impressive collections of restored

old facades, tastefully remodeled interiors,

gleaming towers, fountains, designed open

spaces. Forty- to 60-story towers dwarfed

the rail-era skyscrapers of 12 to 18 floors.

The buildings were monumental and their

functions diverse: offices, hotels, shops, pedestrian

malls, auditoriums, sports arenas, concert

halls, theaters, housing, enclosed skyways.

The Metropolitan Council estimated that

resident population in and adjacent to the downtowns

would grow by 25,000 in the 1980s and

early 1990s. The boom had produced at least

$2 to $3 billion in private and public investment

in the inner city. A large share was downtown,

but the flow to housing and public improvement

in the neighborhoods was also large.

New construction in the central cities accounted

for perhaps one-third of the metropolitan

total from the mid-1970s to the early 1980s. While the greater part of

residential building continued in the suburbs,

all new housing in the inner city was for

replacement. There was no net

population growth. The result was a

very high replacement rate. At the same

time, nearly half of the office space expansion in the 1970s, and more than half of that

projected for the 1980s, was located in the inner-city

downtowns.

The

chronology suggests three historical-geographical

stages in post-World War II metropolitan

development. The first stage was

an all-out effort to house the war veterans' families

after 15 years of neglected construction.

In the second stage, while residential growth continued, the new outer city

caught up with the

backlog of nonresidential construction needs that had been postponed during

the frenetic postwar housing boom. Through

both stages operation of the metropolis

continued to wear out the inner city, while it

concentrated on building the outer city. In the third stage, attention turned to

rebuilding the inner

city. Never before had the problems of aging,

maintenance, preservation, and replacement

been recognized so clearly and attacked

with so much coordination and money.

The

Urban Countryside

While

cities were realigning internally to adapt

to auto-era changes, there was additional

realignment in the neighboring countryside.

Good

roads not only got the farmers out of the

mud, but also brought whole counties or multicounty

shopping trade areas into easy commuting

distance from urban centers. As a result,

many people moved to the rural areas to

live. Many others, who had grown up in rural

areas, found work in the cities but established

their homes on familiar soil and began to

commute. In an earlier generation, they would have migrated to the city; in the

auto era they were long-distance commuters.

As

a result, cities could not expand their boundaries

far enough, fast enough to encompass

the dispersal of urban population. The region's

urban centers, with populations over 2,500

in 1920, enlarged their city limits to accommodate

1.2 million more people by 1980. But

that was less than half the nonfarm population

growth in their own counties during that

period. Urban population obviously burst out

of the municipal cage, especially in the densely

populated eastern half of the region and

the Western Montana Valleys.

(p.

163)

More

than half of the dispersal occurred in the

Twin Cities area. Minneapolis, St. Paul, and

the suburbs already incorporated in 1920 added only 350,000 population from 1920

to 1980. Meanwhile the

seven-county area added 1.3

million. The two central cities made almost no

significant changes in their boundaries, and most of the streetcar suburbs

changed very little. Obviously, about 900,000 population

spilled into previously unincorporated territory.

Similar

dispersal occurred around the smaller

urban centers. For example, in the Southern

Minnesota urban cluster, Owatonna let

out its corporate belt to accommodate a population

increase of 11,000 in 60 years. But annexation

did not encompass all the growth. Another

5,000 built new homes in farm wood-lots

and on gentle hillsides among the corn fields,

converted old farmhouses, pumped new

life into small towns and hamlets, or hooked

up in mobile home courts on the outskirts.

Another example, in the Minnesota Lakes

urban cluster, Brainerd city population grew

only 2,000 from 1920 to 1980, but more than

20,000 were added to the nonfarm population

of the surrounding county. Ninety percent of the urban area's growth followed

the blacktop arterials

and sand side roads to lakeshore and pine

woods outside the city limits. Even the

declining areas experienced similar urban dispersal.

In

every case growth spread into rural townships,

hamlets, and small towns alike. Most

of the urban pioneers in the Twin Cities area

quickly organized new municipalities to resolve mounting community problems—to

pave streets, lay sewer and water

lines, build schools. But at lower densities around the smaller

cities, few people felt any need to organize new municipalities. As a result,

many state and county roads became in fact the streets

of extended urban areas. Consolidated school

districts reflected extended urban communities.

County sheriffs' offices began to operate

urban police services for urban areas dispersed outside the city limits.

Utilities and merchants had to adjust

their rates and charges to be able to

provide urban services in rural

areas. Each of these communities reorganized

to provide a framework for urbanization of the countryside.75

Thus

community decisions and actions, both

private and public, provided the framework

for dealing with growth and decline. The decisions

and actions were needed in the medium

and large growth centers, the declining

or nongrowth cities, the regional metropolis

and the urbanizing countryside.

In the process of settlement, the map of places

and populations became a map of geographic

communities. Each community was anchored

to its place by the long life-expectancy

of the buildings that people have put there,

by the commitments of people there to one

another, and by their affection for the place

itself. When a crisis makes part of the place obsolete, some individuals can

adapt by moving on to another place. But a community rooted

in a place cannot move. The core of the community turns out to be the

group that is anchored there at any given

time by the buildings and by fixed

commitment and affection. That group

has to provide the current of continuity

in the turbulent demographic stream. And it is that group, at any given time and

place, who creates the framework for dealing with

problems of growth and decline.